Coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) have become faster. The holes to be measured have become smaller (think fuel injection systems). But no matter what challenges crop up, parts still need to be measured, quickly and accurately. And styli have adapted.

Though small and seemingly insignificant, styli can take down the best of CMMs. “We see it over and over again,” says Frank Richter, executive director of Carl Zeiss 3-D Automation GmbH (Essingen, Germany). “You can buy a very sophisticated CMM in production, but if you use the wrong styli, it will destroy the accuracy of the whole machine. You will not be able to measure the specification that the machine has.”

So don’t underestimate the component. After all, “You cannot use the machine unless you have a stylus attached to the probe,” says Dennis Bobo, business development and senior applications engineer at Renishaw (Hoffman Estates, IL). “The machine is basically dead in the water without the stylus.”

Select Your Styli

Though styli selection is specific to each application, some overall guidelines do apply. Three basic requirements for the stylus stem are that it should be light, stiff, and thermally stable.

The stylus stem is typically made of stainless steel, tungsten carbide, ceramic or carbon fiber, while the ball is usually ruby, silicon nitride, diamond, or zirconia. Try the standard material and then work up to the higher-end ones if needed, says Andreas Holowitz, manager of marketing and sales at Carl Zeiss 3-D Automation. Ruby works for many different applications, but if that doesn’t work, go to silicon nitride, and from there, diamond. As the cost of ruby goes up in the larger sizes, ceramic becomes more cost-effective and can be a good choice for balls 10 millimeters and larger.

“The first question I ask the customer is what material they are inspecting,” says Bobo. “Then I can recommend the correct ball material.”

When the probe is dragging across the surface of a part during a scan—as opposed to using a touch trigger method—material selection is especially important. Aluminum might build up on the ruby tip, compromising the styli’s measurement. Wear could be caused by adhesion or abrasion. The styli could pick up the material that it is measuring, or the part could wear down the styli.

Q-Mark Manufacturing Inc. (Mission Viejo, CA) received a patent for drilled silicon nitride balls in 2003, and the company has seen growing interest since then. “It’s vastly superior to ruby in applications that are abrasive or measuring soft materials,” says Q-Mark President Mark Osterstock. It works well when scanning aluminum, and customers have reported that it outlasts ruby five to one. However, it also carries about a 50% price premium, so Osterstock says it is best for production environments where the CMM is constantly in use.

Though materials are important, so is the overall styli construction. Small forces—such as gluing gaps or soft materials—will cause someone to lose the accuracy for the workpiece. In addition, experts suggest using one with as few interfaces as possible.

“The most emphatic trend is in reducing the number of components in a stylus assembly,” Osterstock says. “Traditionally we used extensions or knuckles to bend or twist. Now customers are demanding that all in one piece. The benefit is less things to go wrong because there are less flex points.”

Bob Hospadaruk, CMM metrologist at Hexagon Metrology Inc. (Wixom, MI), agrees. He reminds customers that if they need a 30-millimter probe, don’t use a 20-millimeter probe with a 10-millimeter extension. The goal is to avoid extensions whenever possible.

This trend leads to a completely different method of manufacturing, says Osterstock. A company like General Motors will provide drawings for these one-off parts, which, rather than just assembling parts, the styli manufacturer will then treat the order as an engineering project.

Peter Schlafly, owner of itp styli (St. Louis), says cycle time is another factor to consider, especially in automotive applications. Companies want to maximize the number of measurements that can be taken with one configuration.

Though customers often know what they want when designing their own custom styli, sometimes the styli manufacturers say they have to rein customers in and remind them not to go beyond the limits of physics. Don’t pick a stylus that is too long or heavy.

“The classic tip is always use the shortest and biggest, fattest stylus you can to maximize rigidity,” Osterstock says.

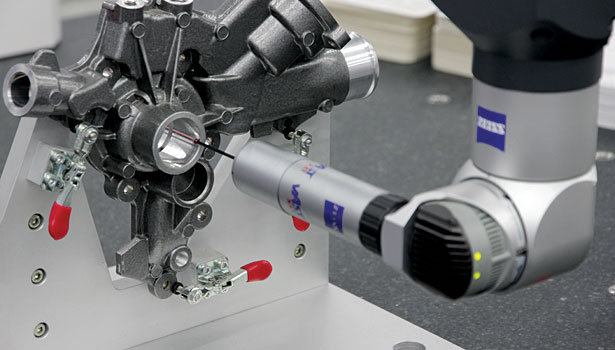

In addition, consider the reach of the styli. “The points that you can reach with the stylus determines if you can measure it,” says Richter. “If you cannot reach a feature on a part with a stylus, you cannot measure it. That has increased the requirements on the styli.”

Handle with Care

Selecting a stylus is only part of the task. Treating them well is equally important. Customers have been spotted storing styli in their desk drawer—not a good idea to have a precision part rolling around—rather than in a specific safe location. Though the very hard ruby tips may seem indestructible, they can have micro fractures if dropped and should be treated like the precision components they are, says Hospadaruk.

Cleaning styli is another good idea, especially in contaminant-type production environments. Wipe the styli off carefully with a lint-free cloth and some alcohol, and be careful not to damage it in the process.

But sometimes cleaning won’t fix the issue; styli should be retired before they cause problems. Too often, Hospadaruk says he sees styli measuring too many parts, for too long.

Finally, remember that styli are only one part of a larger interconnected system.

“People sometimes get a little over focused on the stylus,” says Richter. “We have recognized that it’s very important nowadays for the people using CMMs to look into what accessories are available, workpiece fixturing, styli storage and so on. So many things influence the productivity of the CMM.”

Michelle Bangert is the managing editor of Quality Magazine.

Quality 101: The Styli Basics